Bell was 10 years old when she killed Brown and 11 when she killed Howe, making her one of Britain’s most notorious child killers. Released in 1980.

Mary Bell grew up in the Scotswood area of Newcastle, an economically depressed area where domestic violence and criminal behavior was commonplace. Scotswood had barely changed since the war. It was a slum area with all the social problems that come, with years of neglect and deprivation. There were a lot of notorious families in the areas who were well known to the police for drunkenness, minor petty crimes and that sort of thing.

A lot of pubs in that area, a legacy from the days of the factory, the heavy industrial area and it was common for husbands to be drunk and calls to the police were very frequent for the responds to fights in the house and the streets. Mary Bell lived in a bad area, parked near every other house was house of the prostitute of some sort, White House Road. It was the roughest part of a rough estate. Children there were left to play unsupervised for hours in the streets. It was a time of growing prosperity in Britain, but the new wealth never came to New Castle’s West End. Then, New Castle was in the grip of massive redevelopment. The worst slums were being knocked down to make way for new high-rise flats. The demolition sites, rat alley became a children’s playground as the city changed by the day. As a result, her previous crimes, including attacks on other children at school, vandalism and theft did not attract undue attention. Poverty could have been seen everywhere.

Mary Bell’s mother, Betty, was a prostitute who was often absent from the family home, travelling to Glasgow to work. Independent accounts from family members suggest strongly that Betty had attempted to kill Mary and make her death look accidental more than once during the first few years of her life. The Bell home, in Newcastle, England, was filthy and sparsely furnished. Mary was her first child, born when she was sixteen years old. Mary’s mother was depressive and erratic and on one occasion she tried to have Mary adopted, yet on another she rejected her family’s offers to take a daughter off her hands. It is not known who Mary’s biological father was, according to one source, and for most of her life she believed it to be Billy Bell, an habitual petty criminal and a drunkard, later arrested for armed robbery, who had married Betty sometime after Mary was born. It is important to know that Mary Bell is a source of many information we have about sexual abuse by her mother, a prostitute who specialized as a dominatrix (woman who has dominant role in SM sexual activities), and her mother’s clients who, allegedly, molested her. She was paid a reported £50,000 for collaborating with author of a book about her.

Mary’s disturbed behavior was well known in the playground. Mary used to fix children with a stare and she has a distinctive blue eyes.

People who knew her from those years say that when she had fixed them, they had know they had been in trouble. She played with other children, something, maybe, upset her and she became aggressive. Children were afraid of her and tried to keep away from her, but there were situations she came to them. Also, she would have act funny, she would have shook the head and then she knew who to get by the throat. She chocked one girl, she was red in her face, lips changed a colour but they saved her. As adults, once children, made an impression that she easy manipulated children. Mary’s teachers knew she seemed to have a sadistic streak. One morning, a child came at the class and had a mark on her cheek. Mary had stepped out a cigarette on her cheek. Mary said she had felt sorry.

At school, Mary became known as a pathological liar and disruptive pupil. On occasion, she voiced her desire “to hurt people.”

The cruel urge surfaced May 11, 1968, when Mary and Norma Bell (who was no relation, less bright, although 2 years older than Mary and she followed Mary) were playing with a three-year-old boy on the top of a Newcastle air raid shelter. The boy was severely injured, but the incident was written off as accidental. A Mother of a local girl complained to the police that Mary Bell had attempted to strangle her daughter. Again nothing was done. She got a sand and poured at the mouth. Police were called and nothing, because children were afraid of telling the truth. On May 12, the mothers of three young girls informed police that Mary had attacked and choked their children.

She was interviewed and lectured by authorities, but no juvenile charges were filed.

Mary’s method was to massage the neck of the boys and tell them that is so throat and that should make it better and her grip tightened and tightened until it cause the death.

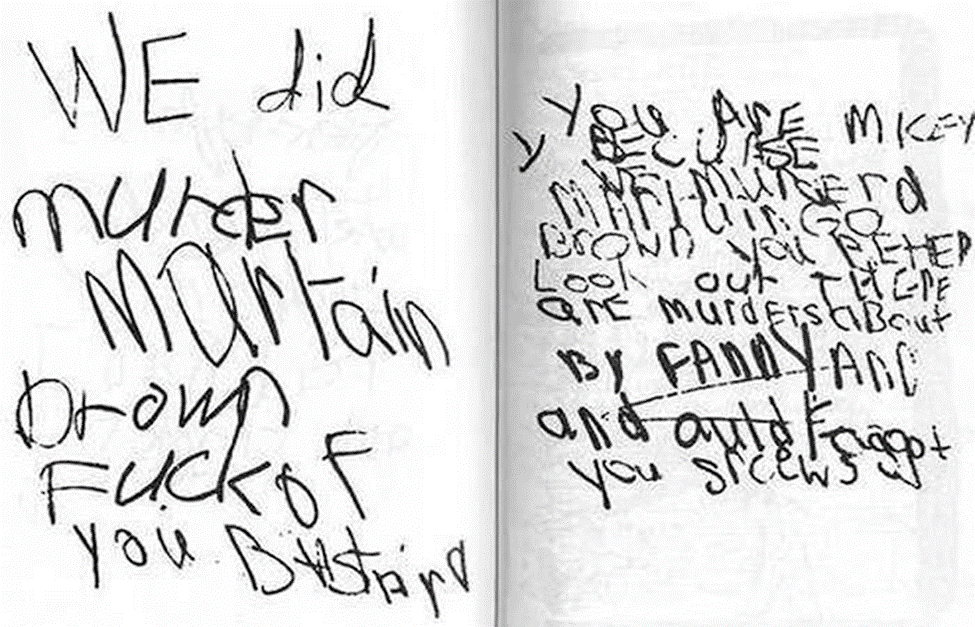

On 25 May 1968, the day before her 11th birthday, Mary Bell strangled four-year-old Martin Brown in a derelict house. She was believed to have committed this crime alone. On May 26, Norma Bell’s father caught Mary choking his 11-year-old daughter; he slapped her face and sent her home. Later that day, she and a friend, Norma Joyce Bell (no relation), aged 13, broke into and vandalized a nursery in Scotswood, leaving notes that claimed responsibility for the killing.

Mary Bell’s note

The police dismissed this incident. Four days later, Mary Bell appeared at the Brown’s residence, asking to see Martin, reminded of the tragedy. She told his grieving mother: “Oh, I know he’s dead. I wanted to see him in his coffin.“

Also, she had developed a reputation as a “show off”, so her proclamation, “I am a murderer” was dismissed as just another one of her idle boasts.

On May 31, a newly-installed burglar alarm at the vandalized nursery school brought patrolmen rushing back to the scene, where they found Mary and Norma Bell loitering beside the building.

Both girls fervently denied involvement in the previous break-in, and they were released to the custody of their parents.

On 31 July 1968, the pair took part in the death, again by strangling, of three-year-old Brian Howe, on wasteland in the same Scotswood area. An immediate search was mounted, and Mary Bell told Brian’s sister, Pat, that he might be playing on a heap of concrete blocks that had been dumped out on a nearby vacant lot. Mary Bell wanted Pat to discover her dead brother, Norma later said, “because she wanted Pat Howe to have a shock.” In fact, The Newcastle Police found his body there at later that night, among the tumbled slabs, but he was dead. Brian was found covered with grass and purple weeds. He had been strangled. The wounds were bizarre: “M” had been carved on boy’s belly with a razor blade. This cut would not be apparent until days later. It appeared that someone had carved an “N”, and that a fourth mark was added to change the “N” into a “M”. There were puncture marks on his thighs, and his genitals had been partially skinned. Clumps of his hair were cut away. Nearby, a pair of broken scissors lay in the grass. A medical examiner suggested that the killer might have been a child, since relatively little force was used. Among the children who stood out as suspicious to the investigators were eleven year old Mary Bell and thirteen year old Norma Bell (no relation). Brian Howe was buried on August 7th. Detective Dobson was there and said: “Mary Bell was standing in front of the Howe’s house when the coffin was brought out. I was, of course, watching her. And it was when I saw her. She stood there, laughing. Laughing and rubbing her hands. I thought, My God, I’ve got to bring her in, she’ll do another one.” Mary Bell was evasive and acted strange. Norma was excited by the murder, remembers one authority. “She was continually smiling as if it was a huge joke.”

“Brian Howe had no mother, so he won’t be missed”, said Mary Bell.

Answers from Mary and Norma Bell were inconsistent, and both girls were brought in for questioning. While Mary claimed that she had seen an older boy abusing Brian, Norma soon broke down and told of watching Mary kill the boy.

As the investigation narrowed on Mary, she suddenly “remembered” seeing an eight year old boy with Brian on the day he died. The boy hit Brian for no reason, she claimed. She had also seen the same boy playing with broken scissors. But that boy had been at the airport on the afternoon Brian died.

An open verdict had originally been recorded for Martin Brown’s death as there was no evidence of foul play—although Bell had strangled him, her grip was not hard enough to leave any marks. Eventually, his death was linked with Brian Howe’s killing and in August 1968 the two girls were charged with two counts of manslaughter.

On 17 December 1968, at Newcastle Assizes, Norma Bell was acquitted but Mary Bell was convicted of manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility, the jury taking their lead from her diagnosis by court-appointed psychiatrists who described her as displaying “classic symptoms of psychopathy”. The judge, Mr. Justice Cusack, described her as dangerous and said she posed a “very grave risk to other children”. She was sentenced to be detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure, effectively an indefinite sentence of imprisonment.

She was initially sent to Red Bank secure unit in St. Helens, Lancashire — the same facility that would house Jon Venables, one of James Bulger’s child killers, 25 years later.

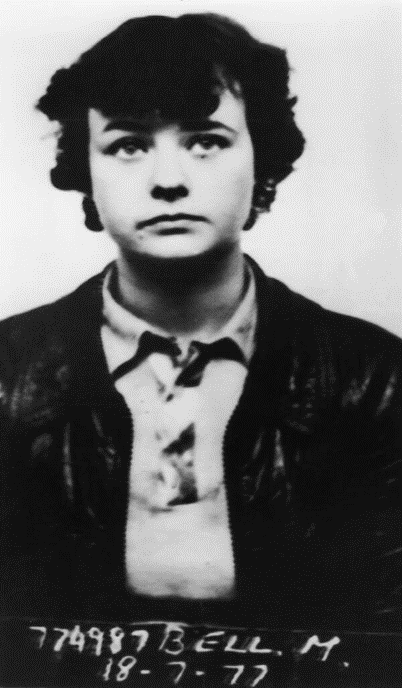

Described by court psychiatrists as “intelligent, manipulative, and dangerous,” Mary proved it was true. In 1970, she fabricated charges of indecent assault against one of her warders, but the man was acquitted in court. In September 1977, she escaped from Moor Court open prison with another inmate, but the runaways were captured three days later. After her conviction, Bell was the focus of a great deal of attention from the British press and also from the German Stern magazine. Her mother repeatedly sold stories about her to the press and often gave reporters writings she claimed to be Mary’s.

Bell herself made headlines when, in September 1977, she briefly absconded from Moore Court open prison, where she had been held since her transfer from a young offenders institution to an adult prison a year earlier. Her penalty for this was a loss of prison privileges for 28 days.

In the meantime, they had met two boys with whom they spent the night, a circumstance that placed Mary back in tabloid headlines, offering a blow-by-blow account of how she gave up her virginity.

In 1980, Bell, aged 23, was released from Askham Grange open prison, having served 12 years. She was granted anonymity (including a new name) to start a new life with her daughter, who was born on 25 May 1984.

Bell’s daughter did not know of her mother’s past until Bell’s location was discovered by reporters and she and her mother had to leave their house with bed sheets over their heads.

Bell’s daughter’s anonymity was originally protected only until she reached the age of 18. However, on 21 May 2003, Bell won a High Court battle to have her own anonymity and that of her daughter extended for life.

Any court order permanently protecting the identity of someone is consequently known as a “Mary Bell order”. In 2009, it was reported that Bell had become a grandmother.

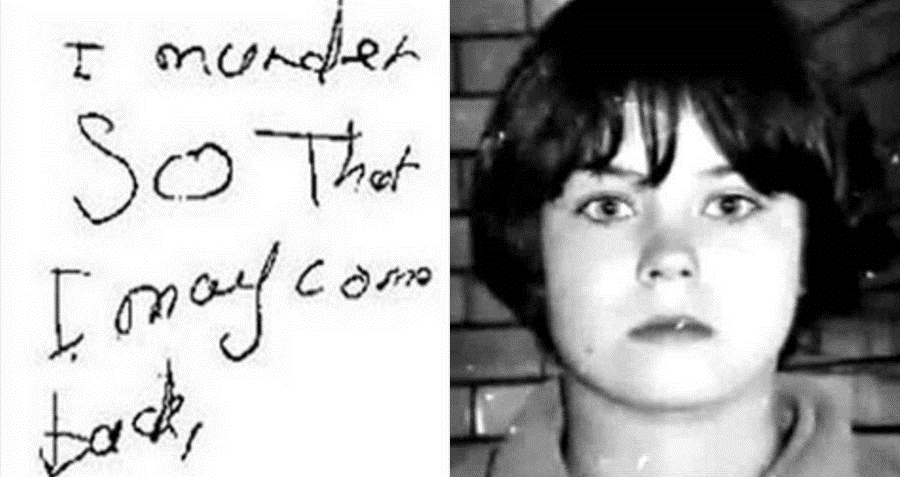

Mary Bell

Bell is the subject of two books by Gitta Sereny: The Case of Mary Bell (1972), an account of the killings and trial, and Cries Unheard: the Story of Mary Bell (1998), an in-depth biography based on interviews with Bell and relatives, friends and professionals who knew her during and after her imprisonment. This second book was the first to detail Bell’s account of The publication of Cries Unheard was controversial because Bell received payment for her participation. In 1998, , Cries Unheard, which detailed her life. She was tracked down amid calls for her right to anonymity to end. The payment was criticized by the tabloid press, and Tony Blair’s government attempted to find a legal means to prevent its publication on the grounds that a criminal should not profit from his or her crimes, but the attempt was unsuccessful.

Bell’s brief prison escape was the basis for a Screen Two teleplay on the BBC, Will You Love Me Tomorrow (1987), starring Joanne Whalley as the tough yet oddly innocent escapee who has come of age behind bars and goes looking for love in a seaside resort town.

Bell’s case (as well as the murder of James Bulger) was used as the basis for a 1999 episode of Law & Order. Bell’s case was also used as the basis for an episode of the short-lived 2005 series entitled “Everything Nice” Bell was also the basis for several songs written by extreme metal band Macabre on their 1993 album Sinister Slaughter, and is also the subject of the Perfume Genius song “Look Out, Look Out”. The seminal industrial artist Monte Cazazza named one of his songs after Bell.

Bell’s case was the basis for a short story titled “Blue Eyes” by Jay Caselberg that aired on Pseudopod on September 2nd, 2011.

From BBC’s ‘Children Of Crime’ series (1998).