Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus has been particularly concerned with how subsequent information can affect an eyewitness’s account of an event.

Loftus’ findings indicate that memory for an event that has been witnessed is highly flexible. If someone is exposed to new information during the interval between witnessing the event and recalling it, this new information may have marked effects on what they recall. The original memory can be modified, changed or supplemented.

The fact that eyewitness testimony can be unreliable and influenced by leading questions is illustrated by the classic psychology study by Loftus and Palmer (1974), Reconstruction of Automobile Destruction, described below.

They were then asked specific questions, including the question “About how fast were the cars going when they (smashed / collided / bumped / hit / contacted) each other?”

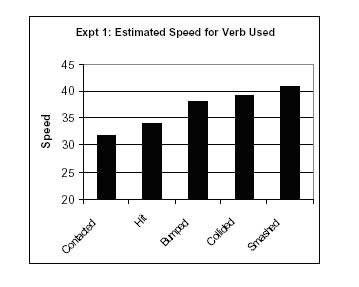

The verb implied information about the speed, which systematically affected the participants’ memory of the accident.

Participants who were asked the “smashed” question thought the cars were going faster than those who were asked the “hit” question.

The participants in the “smashed” condition reported the highest speed estimate (40.8 mph), followed by “collided” (39.3 mph), “bumped” (38.1 mph), “hit” (34 mph), and “contacted” (31.8 mph) in descending order.

Conclusion

The results show that the verb conveyed an impression of the speed the car was traveling and this altered the participants” perceptions.

In other words, eyewitness testimony might be biased by the way questions are asked after a crime is committed.

Loftus and Palmer offer two possible explanations for this result:

Response-bias factors: The misleading information provided may have influenced the answer a person gave (a “response-bias”), but didn’t actually lead to a false memory of the event. For example, the different speed estimates occur because the critical word (e.g., “smash” or “hit”) influences or biases a person’s response.

The memory representation is altered: The critical verb changes a person’s perception of the accident—some critical words would lead someone to perceive the accident as more serious. This perception is then stored in a person’s memory of the event.

If the second explanation is true, we expect participants to remember other details that are not. Loftus and Palmer tested this in their second experiment.

Experiment Two: The Broken Glass Manipulation

A second experiment was conducted with the aim of investigating is leading questions simply create a response bias, or if they actually alter a person’s memory representation?

150 students were shown a one-minute film which featured a car driving through the countryside followed by four seconds of a multiple traffic accident.

Afterward, the students were questioned about the film. The independent variable was the type of question asked.

50 participants were asked “how fast were the car going when they hit each other?”,

50 participants were asked, “How fast were the cars going when they smashed each other?”

The remaining 50 participants were not asked a question about the car’s speed (i.e., the control group).

One week later, the dependent variable was measured – without seeing the film again, they answered ten questions, one of which was a critical one randomly placed in the list:

“Did you see any broken glass? Yes or no?”

There was no broken glass in the original film.

Participants were asked how fast the cars were going when they smashed were more likely to report seeing broken glass.

This research suggests that questioning techniques easily distorts memory, and information acquired after an event can merge with original memory, causing inaccurate recall or reconstructive memory.